It’s finally happened. I did a proper JavaScript thing. Now before you start to judge me, let me clarify that although I’ve never written a JavaScript post ever, it’s not like I don’t know how to use it, okay? Sure I started out with jQuery back in 2015, big whoop, almost everybody I know has used jQuery at some point in their careers 😤.

In fact, my superficial need for external validation made me so self-concious about using jQuery in 2015 that I soon treated Ray Nicholus’s You Don’t Need jQuery! like some holy reference for a while until I weaned myself off jQuery.

But that’s beside the point. Up till now, I’ve always been doing client-side JavaScript. I’d partner up with a “JavaScript person” who would handle the middleware-side of things, and write the nice APIs I would consume and be on my merry way. I’m pretty much known for my inordinate love of all things CSS, because I took to it like a duck to water 🦆.

Learning JavaScript was like being a duck trying to fly. Zoology lesson: ducks can fly! It’s just that they’re not optimised for flying at will. But on the whole, it is obvious that ducks can fly and may even take wing at a fast pace of about 50 miles per hour. So after a couple years, I felt it was time to stand on my own two feet and figure out how this middleware-server-api-routing stuff worked.

The use case

Everybody and their cat can build or has built an app, right? The time had come for me to join that club. I’d been tracking the list of books I want to read/borrow from the world-class Singapore National Library with a plain text file stored on Dropbox. It worked great till the list grew to past 40 books. The solution to this unwieldy list was obvious: (so say it with me) Just build an app for that.

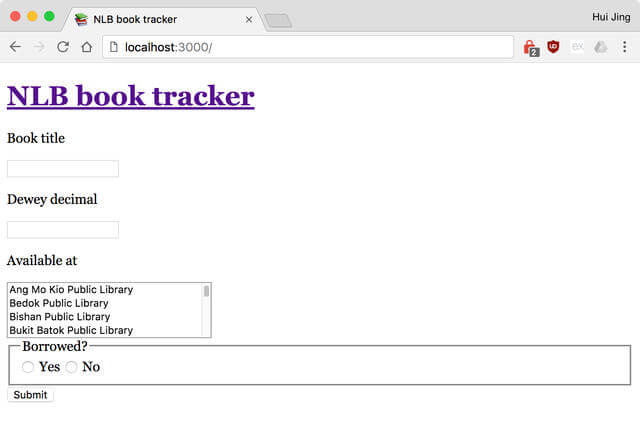

To track list of books by title, dewey decimal number and available locations

That was the basic gist of the idea. The key functionality I wanted was to be able to filter the list depending on which library I was visiting at the time, because some books had copies in multiple libraries. Critical information would be the book title and dewey decimal number to locate said book. Simple enough, I thought. But it never is.

This being my first ”app”, I thought it’d be interesting to document the thought process plus questions I asked myself (mostly #noobproblems to be honest). Besides, I never had a standard format for writing case studies or blog posts. I also ramble a lot. Source code if you really want to look at noob code.

TL:DR (skip those which bore you)

- Technology stack used: node.js, Express, MongoDB, Nunjucks

- Starting point: Zell’s intro to CRUD tutorial

- Database implementation: mLAb, a hosted database solution

- Templating language: Nunjucks

- Data entry: manually, by hand

- Nunjucks syntax is similar to Liquid

- Responsive table layout with HTML tables

- Filtering function utilises

indexOf() - Implementing PUT and DELETE

- Offline functionality with Service Worker

- Basic HTTP authentication

- Deployment: Heroku

What technology stack should I use?

I went with node.js for the server, Express for the middleware layer, MongoDB as the database because I didn’t really want to write SQL queries and Nunjucks as the templating language because it’s kind of similar to Liquid (which I use extensively in Jekyll).

But before I settled on this stack, there was a lot of pondering about data. Previously, I had been terribly spoiled by my JavaScript counterparts who would just pass me endpoints from which I could access all the data I needed. It was like magic (or just abstraction, but aren’t the two terms interchangeable?).

I’m used to receiving data as JSON, so my first thought was to convert the data in the plain text file into a JSON file, then do all the front-endy stuff I always do with fetch. But then I realised, I wanted to edit the data as well, like remove books or edit typos. So persistence was something I didn’t know how to deal with.

There was a vague memory of something related to SQL queries when I once peeked into the middleware code out of curiosity, which led me to conclude that a database had to be involved in this endeavour 💡. I’m not as clueless as I sound, and I know how to write SQL queries (from my Drupal days), enough to know that I didn’t want to write SQL queries for this app.

You have no idea how to write this from scratch, do you?

Nope, not a clue. But my buddy Zell wrote a great tutorial earlier on how to build a simple CRUD app, which I used as a guide. It wasn’t exactly the same, so there was a lot of googling involved. But the advantage of not being a complete noob was that I knew which results to discard and which were useful 😌.

Zell’s post covers the basic setup for an app running on node.js, complete with idiot-proof instructions on how to get the node.js server running from your terminal. There’s also basic routing, so you can serve the index.html file as your home page, which you can extend for other pages as well. Nodemon is used to restart the server every time changes are made so you don’t have to do it manually each time.

He did use a different stack from me, like EJS instead of Nunjucks, but most of the instructions were still very relevant, at least in part 1. Most deviations happened for the edit and delete portion of the tutorial.

So this mLab thing is a hosted database solution?

Yeah, Zell used mLab in the tutorial, it’s a Database-as-a-Service so I kinda skipped over the learning how to set up MongoDB bit. Maybe next time. Documentation on how to get started using mLab is pretty good, but one thing made me raise an eyebrow (omg, when is this emoji coming?!), and that was the MongoDB connection URI contained the user name and password to the database.

I’m not a security expert but I know enough to conclude that is NOT a good idea. So next thing to find out was, what is the best way to implement this as a configuration? In Drupal, and we had a settings.php file. Google told me that StackOverflow says to create a config.js file then import that for use in the file where you do your database connections. I did that at first, and things were peachy, until I tried to deploy on Heroku. We’ll talk about this later, but point is, store credentials in separate file and do NOT commit said file to git.

You don’t want to use EJS like Zell, then how?

It’s not that EJS is bad, I just wanted a syntax I was used to. But not to worry, because most maintainers of popular projects dedicate time to writing documentation. I learned the term RTFM quite early on in my career. Nunjucks is a templating engine by Mozilla, which is very similar to Jekyll’s (technically Shopify made it) Liquid. Their documentation for getting started with Express was very understandable to me.

Couldn’t think of a way to automate data entry?

Nope, I could not. I did have prior experience doing data entry in an earlier era of my life, so this felt…nostalgic? Anyway, the form had to be built first. Book title and dewey decimal number were straight-forward text fields. Whether the book had been borrowed or not would be indicated with radio buttons. Libraries were a bit trickier because I wanted to make them a multi-select input, but use Nunjucks to generate each option.

After building my nice form, and testing that submitting the form would update my database. I grabbed a cup of coffee, warmed up my fingers and went through around half an hour of copy/paste (I think). I’m very sure there is a better way to generate the database than this, but it would have definitely taken me longer than half an hour to figure out. Let’s KIV this item, okay?

Can you Nunjucks like you do Liquid?

Most templating languages probably can do the standard looping and conditionals, it’s just a matter of figuring out the syntax. In Jekyll, you chuck your data into .yml or .json files in the _data folder and access them using something like this:

{% for slide in site.data.slides %}

<!-- markup for single slide -->

{% endfor %}Jekyll has kindly handled the mechanism for passing data from those files into the template for you, so we’ll have to do something similar for using Nunjucks properly. I had two chunks of data to send to the client-side, my list of libraries (a static array) and the book data (to be pulled from the database). And I learned that to do that we need to write something like this:

app.get("/", (req, res) => {

db.collection("books")

.find()

.toArray((err, result) => {

if (err) return console.log(err);

res.render("index", {

libraries: libraries,

books: result,

});

});

});I’m fairly confident this is an Express functionality, where the render() function takes two parameters, the template file and an object which contains the data you want to pass forward. After this, I can magically loop this data for my select dropdown and books table in the index.html file. Instead of having to type out an obscenely long list of option elements, Nunjucks does it for me.

<select name="available_at[]" multiple>

{% for library in libraries %}

<option>{{ library.name }}</option>

{% endfor %}

</select>

And another 💡 moment happened when I was working out how to render the book list into a table. So the libraries field is a multi-value field, right? As I made it a multi-select, the data is stored in the database as an array, however, single values were stored as a string. This screwed up my initial attempts at formatting this field, until I realised it was possible to force a single value to be stored as an array using [] in the select’s name attribute.

Better make the list of books responsive, eh?

Yes, considering how I pride myself in being a CSS person, it’d be quite embarrassing if the display was broken at certain screen widths. I already had a responsive table setup I wrote up previously that was made up of a bunch of divs that pretended to be a table when the width was wide enough. Because display: table is a thing. I know this because I researched it before.

So I did that at first, before realising that the <table> element has extra properties and methods that normal elements don’t. 💡 (at the rate this is going, I’ll have enough light bulbs for a nice chandelier). This doesn’t have anything to do with the CSS portion of things, but was very relevant because of the filtering function I wanted to implement.

Then it occurred to me, if I could make divs pretend to be a table, I could make a table act like a div. I don’t even understand why this didn’t click for me earlier 🤷. Long story short, when things started to get squeezy, the table, rows and cells got their display set to block. Sprinkle on some pseudo-element goodness and voila, responsive table.

Let’s talk about this filtering thing, alright?

I’ll be honest. I’ve never written a proper filtering function by myself before. I did do an autocomplete, once. But that was it. I think I just used someone else’s library (but I made sure it was like really tiny and optimised and everything) when I had to. What I wanted was to have a select dropdown that would only show the books available at one particular library.

The tricky thing was that the library field was multi-value. So you couldn’t just match the contents of the library cell with the value of the option selected, or could you? So I found this codepen by Philpp Unger which filtered a table based on text input.

The actual filtering leverages the indexOf() method, while the forEach() method loops through the whole slew of descendants in the book table. So like I mentioned earlier, a normal HTMLElement doesn’t have the properties that a HTMLTableElement does, like HTMLTableElement.tBodies and HTMLTableElement.rows. MDN documentation is great, here are the links for indexOf(), forEach() and HTMLTableElement.

Why was your edit and delete different from Zell’s?

Because I had more data, and I didn’t want to use fetch for the first pass. I wanted CRUD to work on the basic version of the app without client-side JavaScript enabled. It’s fine if the filtering doesn’t work without JavaScript, I mean, I probably could make it so the filtering was done on the server-side, but I was tired.

Anyway, instead of fetch, I put in individual routes for each book where you could edit fields or delete the whole thing. I referred to this article by Michael Herman, for the put and delete portions. Instead of fetch, we used the method-override middleware.

The form action then looked like this:

<form method="post" action="/book/{{book._id}}?_method=PUT">

<!-- Form fields -->

</form>The form itself was pre-populated with values from the database, so I could update a single field without having to fill the whole form out each time. Though that did involve putting in some logic in the templates, for the multi-select field and my radio buttons. I’ve heard some people say templates should be logic-free, but 🤷.

<select name="available_at[]" multiple>

{% for library in libraries %} {% if book.available_at == library.name %}

<option selected>{{ library.name }}</option>

{% else %}

<option>{{ library.name }}</option>

{% endif %} {% endfor %}

</select><fieldset>

<legend>Borrowed?</legend>

{% if book.borrowed == "yes" %} {{ checked }} {% set checked = "checked" %} {% else %} {{

notchecked }} {% set notchecked = "checked" %} {% endif %}

<label>

<span>Yes</span>

<input type="radio" name="borrowed" value="yes" {{ checked }} />

</label>

<label>

<span>No</span>

<input type="radio" name="borrowed" value="no" {{ notchecked }} />

</label>

</fieldset>One problem that took me a while to figure out was that I kept getting a null value when trying to query a book using its ID from my database. And I was sure I was using the right property. What I learned was, the ID for each entry in MongoDB is not a string, it’s an ObjectID AND you need to require the ObjectID function before using it.

Oooo, let’s also play with Service Worker!

Have you read Jeremy Keith’s wonderful book, Resilient Web Design yet? If you haven’t, stop right now and go read it. Sure it’s a web book, but it also works brilliantly offline. So I’ve known about Service Worker for a bit, read a couple blog posts, heard some talks, but never did anything about it. Until now.

The actual implementation wasn’t that hard, because the introductory tutorials for the most basic of functionalities are quite accessible, like this one by Nicola Fioravanti. You know how when you build a thing and you ask the business users to do testing, and somehow they always manage to do the one obscure thing that breaks things. That was me. Doing it to myself.

So I followed the instructions and modified the service-worker according to the files I needed cached, and tested it out. If you use Chrome, DevTools has a Service Worker panel under Application, and you can trigger Offline mode from there. First thing I ran into was this error: (unknown) #3016 An unknown error occurred when fetching the script, but no biggie, someone else had the same problem on Stack Overflow.

The next thing that tripped me up for a day and a half was that, unlike normal human beings, I reflexively reload my page by pressing ⌘+Shift+R, instead of ⌘+R. That Shift key was my undoing, because it triggers reload and IGNORES cached content. It turned out my Service Worker had been registered and running all this while 🤦♀️.

Ah, the life of a web developer.

Let’s put some authentication on this baby

Okay, I actually took one look at Zell’s demo app and realised it kind of got a bit out of hand because it was a free-for-all form input and anyone could submit anything they wanted. Which was kind of the point of the demo, so no issues there. But for my personal app, I’m perfectly capable of screwing around with the form submission all by myself, thank you.

Authentication is a big thing, in that there are a tonne of ways to do it, some secure and some not, but for this particular use-case I just needed something incredibly simple. Like a htpasswd (you guys still remember what that is, right?). Basic HTTP authentication is good enough for an app which will only ever have one user. Ever.

And surprise, surprise, there’s an npm module for that. It’s called http-auth, and implementation is relatively straight-forward. You can choose to protect a specific path, so in my case, I only needed to protect the page that allowed for modifications. Again, credentials in a separate file, kids.

const auth = require("http-auth");

const basic = auth.basic({ realm: "Modify database" }, (username, password, callback) => {

callback(username == username && password == password);

});

app.get("/admin", auth.connect(basic), (req, res) => {

// all the db connection, get/post, redirect, render stuff

});What about deployment?

Ah yes, this part of development. If you ask me, the easiest way to do this is with full control of a server (any server), accessible via ssh. Because for all my short-comings in other areas (*ahem* JavaScript), I’m fully capable of setting up a Linux server with ssh access plus some semblance of hardening. It’s not hard if you can follow instructions to a T and besides, I’ve had lots of practice (I’ve lost count of the number of times I wiped a server to start over).

But I’m a very very cheap person, who refuses to pay for stuff, if I can help it. I’ve also run out of ports on my router so those extra SBCs I have lying around will just have to continue to collect dust. The go-to free option seems to be Heroku. But it was hardly a smooth process. Chalk it up to my inexperience with node.js deployment on this particular platform.

It was mostly issues with database credentials, because I originally stored them in a config.js file which I imported into my main app.js file. But I realised there wasn’t a way for me to upload that file to Heroku without going through git, so scratch that plan. Let’s do environment variables instead, since Heroku seems to have that built in.

What took me forever to figure out was that on Heroku, you need to have the dotenv module for the .env file to be recognised (or wherever Heroku handles environment variables). Because on my local machine, it worked without the dotenv module, go figure.

Wrapping up

Really learned a lot from this, and got a working app out of it, so time well spent, I say. I also learned that it’s actually pretty hard to find tutorials that don’t use a truck-load of libraries. Not that I’m against libraries in general, but as a complete noob, it’s a bit too magical for me. Sprinkle on the fairy dust a little later, thanks. Anyway, I’ll be off working on the next ridiculous idea that pops into my mind, you should try it some time too 🤓.