Earlier this year, Jen Simmons asked the following question:

From your memory, which browser has now twice the user base of Internet Explorer (globally)? (Don’t cheat — what’s your impression?)

— Jen Simmons (@jensimmons) January 24, 2017

I managed to get the right answer (UC Browser) by virtue of elimination, not because I actually knew the statistics 😆. But what I do know, is that one of the options I have on my phone was not on that list. Yes, this is my semi-fail segue into talking about Opera Mini. Writing is hard 🤷.

Who uses Opera Mini?

Guess what? I do. I’m reasonably confident that I am possibly the only person in Singapore using a BLU Win HD LTE. It currently runs on Windows 10 Mobile, and I like it. Microsoft Edge uses EdgeHTML as its layout engine and Chakra as its JavaScript engine. Both desktop and mobile versions use the same engine, which is more than I can say for iOS browsers 🔥.

Anyway, back to Opera Mini. The browser usage share for February 2017, according to StatCounter is 3.3%. That’s actually more than Edge 14 (1.49%) and Safari 10 (1.54%) combined. Regionally, the lion’s share of users for Opera Mini are from Africa, followed by Asia.

Africa is a significant market for Opera and they have focused on developing features that address key challenges for people in that region: high data costs, limited network capacity, growing page weights and background data consumption. These challenges apply to lower-income countries in other regions as well.

Different modes on Opera Mini

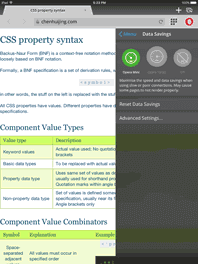

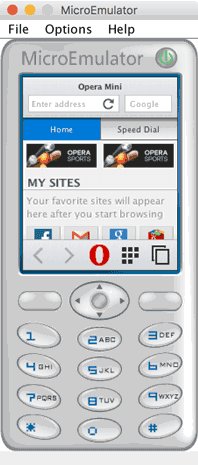

Opera Mini has different modes, which affect data consumption and also rendering. Each of the operating systems uses a version of Opera Mini with a different set of modes. Check out the full table at Opera Browsers, Modes & Engines.

There are 4 Operating Systems that can run Opera Mini: Android, iOS, J2ME and Windows Phone, and 3 different rendering engines depending on which mode is chosen.

Opera Mini also has a built in QR code reader, which I find pretty useful because typing URLs is a pain. I honestly don’t know why so many people think QR codes are useless, but if I can use a QR code to get to a site I will. With my Opera Mini QR code reader 🙆.

Presto, server-side

This version is what runs on J2ME and Windows Phone. It can be selected as Opera Mini mode on iOS and Extreme mode on Android. The most significant feature for this mode is its server-side compression.

Opera Mini can act as a proxy browser, meaning the requests from the browser will go through Opera’s transcoding servers before being forwarded to the website’s server. When the server returns its response, it too passes through Opera’s servers, it gets transcoded into Opera Binary Markup Language (OBML) which then gets progressively loaded on the user’s device.

The transcoding process involves parsing of HTML and CSS, as well as execution of JavaScript. What is received by Opera Mini at the end of it is an “interactive snapshot of the document’s state”. The data savings from this can be up to 90% over the network, but the downsides are standards support is limited, hence quite a few CSS properties are not supported and JavaScript may not behave in ways you expect.

Some people might be concerned with is security, given that all data will pass through Opera’s servers. Opera ensures that the traffic between your handset and their servers is encrypted when browsing secure webpages, but they would require access to the unencrypted version of the webpage to implement compression.

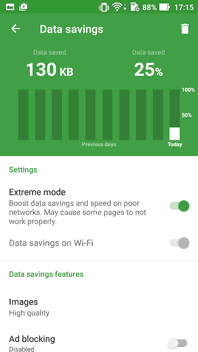

Android WebView

Opera Mini on Android phones also have a High mode option, which runs on Android WebView. WebView is based on Chromium and uses the V8 JavaScript engine. By default, if you are connected to Wi-Fi and using this mode, data savings are disabled unless you explicitly turn it on in the Settings.

There is also something called Video Boost, which is an option you can toggle from the Data Savings settings as well. Activating it will trigger video compression to reduce the size of the video file during the transcoding process.

WebKit, system

Opera Mini on iOS phones have 2 additional modes, Normal and Turbo. Both these modes run on WebKit, as is expected for all browsers on iOS. The difference between them is that Turbo is a proxy browser, which works similarly to Mini mode except that the compression is much less aggressive, allowing websites to generally render as expected.

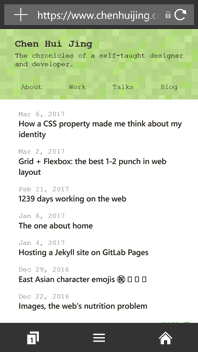

Developing with Opera Mini in mind

This is a recap of my own experience and some thought processes that led to certain decisions. Point is, it’s necessary to understand that there will be people who browse your site using Opera Mini mode. It could be 1 person, it could be 100, it could be 100,000. I’ve often heard the argument that people using Opera Mini are not the target audience so it doesn’t matter.

It does matter. I’m not saying spend months trying to build an Opera Mini specific implementation, nor am I advocating for limiting features simply because Opera Mini doesn’t support them. I want everyone to go ahead and explore and learn the latest and greatest, experiment and build wonderful experiences. But it is a must that the most basic content is accessible from any browser.

When it’s all said and done, if we strip away all the scripts and styles, can people understand your message? Properly structured text and optimised images. That’s the crux of it. Layer on all the styles and effects and animations, go as far as you want, but make sure they are built upon a solid foundation.

@supports is your best friend

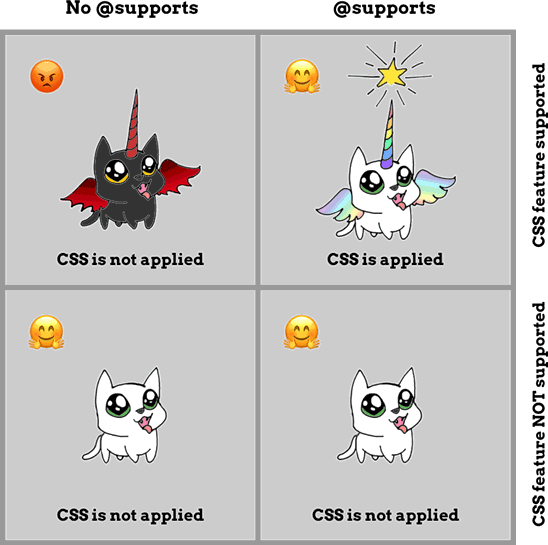

For all the things Opera Mini does not support, the one thing it does have going for it, is @supports. In fact, without @supports (also known as feature queries), life would be a lot harder when it comes to layering on enhancements.

Opera first implemented in Nov 2012. Both Chrome and Firefox had it since May 2013. So people have been writing about feature queries over the years, though it seems that awareness of its broad support is not well-known. In fact, a lot of early coverage was not written in English (maybe that’s why, I can’t say for sure).

- @supports ― CSSのFeature Queries by Masataka Yakura, August 8 2012

- Native CSS Feature Detection via the @supports Rule by Chris Mills, December 21 2012

- CSS @supports by David Walsh, April 3 2013

- Responsive typography with CSS Feature Queries by Aral Balkan, April 9 2013

- How to use the @supports rule in your CSS by Lea Verou, January 31 2014

- CSS Feature Queries by Amit Tal, June 2 2014

- Coming Soon: CSS Feature Queries by Adobe Web Platform Team, August 21 2014

- CSS feature queries mittels @supports by Daniel Erlinger, November 27 2014

Here’s how support looks like right now.

I see you staring at IE

First of all, let me acknowledge that there is still a significant number of organisations that require support of Internet Explorer. Microsoft still continues to support IE11 for the life of Windows 7, 8 and 10. They have, however, stopped supporting older versions since January 12, 2016.

Before we talk about IE11’s lack of support for @supports (see what I did there? 😈), let me introduce the concept of negativity bias. It is also known as the negativity effect.

Bad is stronger than good, as a general principle across a broad range of psychological phenomena.

—Kathleen D. Vohs

Yes, it will be a bit tricky when it comes to using @supports for certain features that fall into that odd matrix of being supported by IE11 yet not in Opera Mini but it’s kind of a weak excuse to throw the baby out with the bathwater and just disregard feature queries altogether. Going “ain’t nobody got time for dat” is NOT the way to do it.

Jen Simmons wrote an extensive article called Using Feature Queries in CSS which discussed such tricky situations, specifically “Browsers that support do not Feature Queries, yet do support the feature in question”.

For cases like those, it really depends on the specific CSS feature you want to use, then make a decision whether it is acceptable to not include that feature even if the browser supports it.

Of course, it depends on the particular use case. Perhaps this is a result we can live with. The older browser gets an experience planned for older browsers. The web page still works.

—Jen Simmons

Planning is required

I’ll be honest here. I don’t use CSS frameworks. I write my styles from a basic boilerplate I developed over the years, which has in turn increased my familiarity with browser support of CSS properties quite a bit, built up from years of referencing caniuse.com constantly throughout development.

My main development browser is Chrome Dev, but the tool I’ve found most indispensable is BrowserSync. As long as a device is on the same local network, you can view the results of your work incrementally on different browsers, making it easier to resolve cross browser issues as they arise. Much less trouble than trying to solve a plethora of bugs at the end.

Opera Mini doesn’t support BrowserSync

I just glance at the various browsers open at the same time to check if anything is amiss. Now, the issue with Opera Mini is that BrowserSync doesn’t work on Mini mode. I would think it is due to the proxy behaviour so it means you have to push code to a live server to see how it would render on Opera Mini.

This may not be the best solution (and I welcome suggestions on better methods) but I use Surge as my Opera Mini test server. Surge offers free static web publishing via the command line and works really well with a git hook. Here’s their documentation. Because I use gulp as my task runner, I already had a package.json file anyway. Once I pushed my code, I could load the test version on Surge on Opera Mini to see how it looked.

Update: I have since read Bruce Lawson’s article on Making websites that work well on Opera Mini and in there are excellent solutions for local development with Opera Mini, as follows

There are other options like localtunnel, which assigns a uniquely publicly accessible URL that proxies all requests to your locally running web server. The URL remains accessible as long as localtunnel and your local web server is running.

To install it, run the following to install it globally:

npm install -g localtunnelThen, use the following command to request a tunnel to your locally running web server (change the port number to whichever you’re using):

lt --port 8000I coupled this with qrcode-terminal, because I’m a lazy sloth. ICYMI, Opera Mini comes with a QR code scanner, folks! So after you get a URL generated by localtunnel, you can run the following in another terminal window to get a QR code of the URL, freeing you of the need to type a long, meaningless URL on your phone.

qrcode-terminal 'GENERATED_URL_GOES_HERE'There is also ngrok, which comes with more features than localtunnel, like allowing you to inspect your traffic, a real-time web UI and so on. I didn’t try this myself, but this seems like a good solid option as well.

IE11 versus Opera Mini

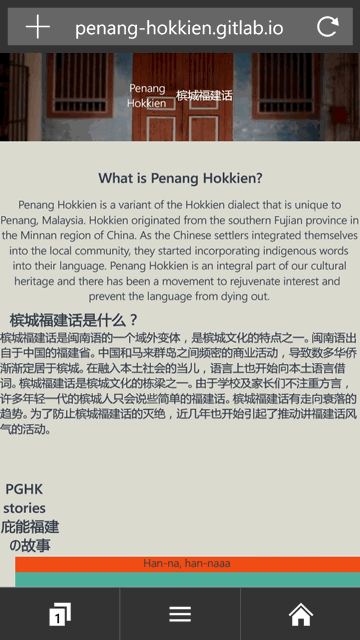

This is the part where decisions need to be made. Building Penang Hokkien was quite the experience for me because there were quite a few CSS features that didn’t play nice across browsers. My language switcher made use of the checkbox hack, which didn’t play well with Opera Mini. And writing-mode isn’t supported either.

But I wasn’t trying to make the Opera Mini site look like how it would on a full-featured browser, I just needed the content to be readable. Opera Mini does not support CSS gradients, which were what my language toggle used. Since the checkbox hack was wonky on Opera Mini to begin with, I turned it off altogether.

@supports (background-image: linear-gradient(to bottom, #f4f1ee, #fff)) {

/* relevant styles here */

}That approach would also turn off the language switcher feature from IE11, because it does not support feature queries, the entire code block is ignored. What is left is that both the Chinese content and English content would be displayed at the same time for Opera Mini and IE11. That’s a decision I could live with.

If you look at my source code, you will notice lots of browser hacks here and there. This is largely due to the fact that there are still a bunch of writing-mode bugs in different browsers. I have styles that are Firefox-specific, Edge-specific, IE11-specific and so on. Is it more code? Yes. I cannot deny that. But at least I get to use the latest CSS features and stil deliver a readable experience to browsers that don’t support them.

There isn’t really a prescribed way to go about developing for cross-browser compatibility. My take is, at least take the time to try out a variety of methods and settle into a workflow you’re most comfortable with. I like using gulp with BrowserSync, you may like something else, and that’s perfectly fine.

Wrapping up

The World Wide Web was originally created as a means for researchers to share information more easily. The concept of information sharing has never wavered over the years. But it is incumbent upon those of us who build for the web to ensure that we aren’t hindering access to information because it is “too much trouble”.

I understand the rationale behind using existing data to determine what browsers you want to support, but sometimes I wonder if doing so results in a cycle of exclusion. That less users of certain browsers visit a site because it doesn’t seem to work right, which makes the developers think it’s not necessary to support that tiny segment anyway. Feels like a death spiral to me.

For sites where the value is in its content, blogs with tutorials, news and articles, I think it’s necessary to make sure your content is still accessible under the most hostile conditions. In the grand scheme of things, it’s really not that hard. Hard is being a refugee fleeing from war, hard is being a migrant worker earning a pittance to support a large family back home, hard is living in fear of being persecuted and attacked because of your faith or race.

No, what we get to do for a living, is a blessing. And making valuable information accessible is the least we can do to help make the world a better place.